Article by Bryony Rheam

Images by Andre van Rooyen, Adam Herscovitz, Veronique Attala

It would be wrong to describe the My Beautiful Home competition as a celebration of traditional Ndebele hut decoration for there is little that is traditional about it. When the AmaNdebele arrived in the area now known as Matabeleland in 1840, they began building their huts in characteristic beehive style: both the sides of the hut and the roof were made of grass. Whilst this design had been effective in KwaZulu Natal, where the Ndebele had originated from, it wasn’t so successful in the hot, dry climate of southern Zimbabwe because the grass from the roof reached the ground making it easy for white ants to attack and destroy in very little time. It was, therefore, out of necessity that they started to consider new ways of building their huts. First, they tried putting a beehive roof on a cylinder hut before finally setting on a cone (roof of the hut) on a cylinder (base and walls). Now that the walls were stand alone and made of mud, not grass, they provided a surface on which to paint.

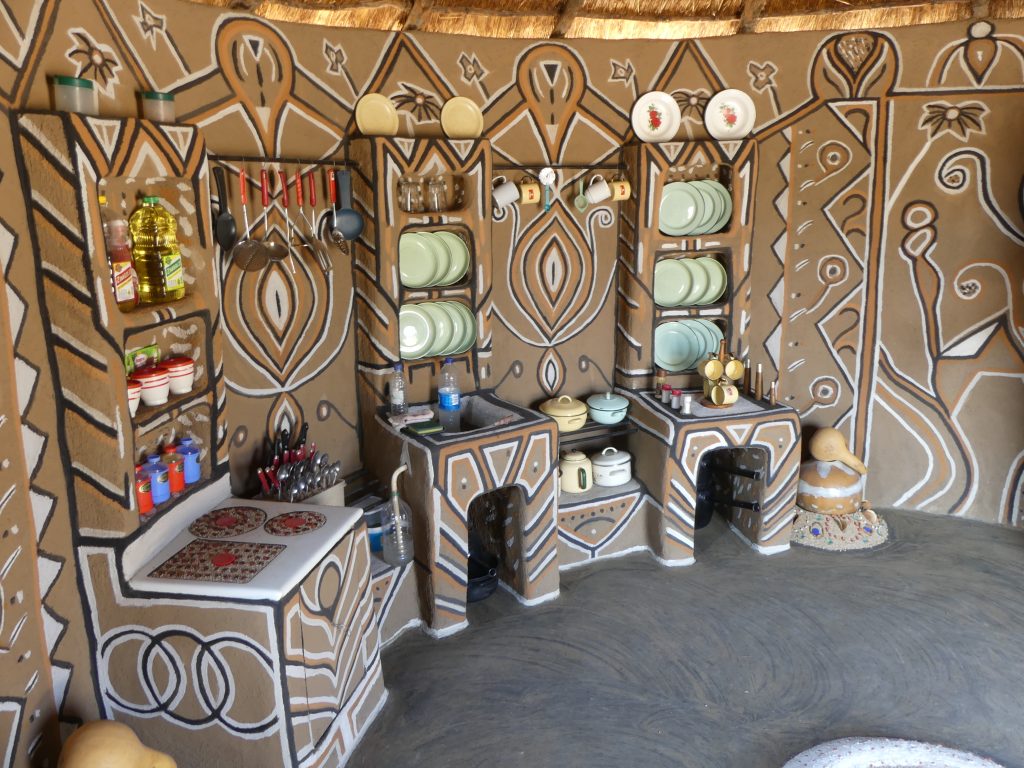

As King Mzilikazi Khumalo had made his way north of the Limpopo, the AmaNdebele had incorporated many Sotho and Tswana people and inevitably their cultural practices were influenced by them, one of them being the decoration of their huts’ external walls. The Banyubi people (an offshoot of the Kalanga) who lived in the Matopos, were already building a cone roof on a cylinder-shaped base. Their unique characteristic was their internal walls which had shelves on which to keep their pots and other cooking instruments. This moulding can still be seen in the modern huts where it has also been extended to include tables, chairs and even ovens and sinks. After being polished with a pebble (imbokodo), the relief is then painted with a mixture made from the bark of the isigangatsha tree which has been boiled with green soap. The Ndebele influence on the huts is restricted to the tiered thatch on the roof and thus what is often referred to as ‘traditional’ is actually an amalgam of different cultures.

According to local historian, Pathisa Nyathi, hut decorations are historically geometric in shape. The colours chosen are red (isibomvu), black (isidaka) and white, made from the ash of the Umtswiri tree. Many of the current designs are of flowers or may include numbers and letters, but the traditional shape is that of the chevron. This pattern may appear to be a simple geometric shape, but it has a much deeper meaning. It is, in fact, a fertility symbol – the ‘v’ shape is symbolic of the legs and the upper part, the womb, of a woman, from where we all began. This is no simple ‘good luck’ motif wishing the inhabitants of the hut a large, healthy family. It also represents continuity of the human race, eternity, and indeed, immortality: individuals perish, humanity is forever. The circular shape of both the huts and the chevron design upon them are inspired, not by human invention, but by the cosmos: the movement of the stars and the planets.

It is a Western concept that art is created for art’s sake. In Africa, art and functionality go together. Pictures communicate a message as well as serve a purpose. Circles, equilibrium and symmetry are all part of African aesthetics which is why a hut is more than just a hut and why a wall is already a thing of beauty, whether it is painted or not. Circles complete the unending cycle of life.

The role of the woman as the source of life, ‘the womb’, is highly prized in traditional life: the painting of the huts is a solely female occupation. When polygamy was the accepted practice, each wife would have her own kitchen hut in which she would cook and sleep. Birth took place in this hut and it is therefore synonymous with the continuation of life. It is also in the kitchen where rituals to propitiate the ancestors are performed. Offerings are left at the back of the kitchen area where nobody is allowed to sit. One person, usually the head of the household, appeals to the ancestors on behalf of the family. The ancestors, in turn, are intermediaries between humans and God, who is not to be appealed to personally. When someone has died, the corpse is placed in the kitchen hut before burial and so completes the unending cycle of life.

Over the past century, the practice of hut decoration has been on the decline and today is only really relevant to the kitchen hut. Many of the bedroom huts are built in a European design – a small rectangular building with a zinc roof. It is unfortunate that modernisation has become synonymous with Europeanisation. Many people do not value rural life anymore and are at pains to eschew their culture. However, the My Beautiful Home competition has gone a long way towards reviving the tradition of hut decoration.

Started by a French lady, Veronique Attala, the competition has been going since 2015. Veronique enjoys going cycling in the Matopos and this is where she discovered a number of people who were still decorating their huts in the traditional way. This was a sign that the people who lived in them were happy and that they loved the place in which they lived. Despite the language barrier and the cultural differences between her and the local people, she felt a oneness, a shared happiness that does not need to be communicated with words. She got in touch with local historian, Pathisa Nyathi, and architect, John Knight, to see if there was any way to revive and celebrate this practice and together they visited the local chief to promote the idea. Soon, other people joined the team, such as Clifford Zulu from The National Gallery, Andre van Rooyen (photography), Violette Kee-Tui and Butholeswi Nyathi. There were thirty entrants in the first year, but by 2016 there were four hundred. There are a number of prizes, including those for the best interior and the best exterior. The prizes comprise of wheelbarrows, kitchenware, water tanks, ploughs, bicycles and torches.

A recent grant from the US Embassy means that a coffee table book detailing the history and tradition behind the decorations and the competition itself will soon be available. Ultimately, however, Veronique wishes that the local people themselves benefit in a wider sense from the competition, by involving them in ecotourism. Interestingly, the means for the local people to improve their lives today relies on the revival of a traditional form of art, but it is a technique that has proved it is open to change. Modern decorations include jigsaw puzzle pieces and even pictures of Christ and Osama Bin laden. As the newly-arrived AmaNdebele were able to adapt to their new environment over a hundred years ago, so, it is hoped, today’s villagers are able to adapt to the demands of the 21st century.

We can provide a guide to go see some of the homes.

A high clearance vehicle is required.

For further information Email: zouero@club.fr

or whatsapp +33603975420